Equal Justice Under Law

As an assistant attorney general, Todd Kim works on some of the country’s most consequential conservation and pollution issues. His unit, the Environment and Natural Resources Division at the Department of Justice, is responsible for bringing charges against violators, defending federal agency actions, and enforcing over 150 laws. Yet even for the environment enthusiast, the division’s work is often not well understood. As former head of ENRD, John Cruden, puts it, “The division is much broader than most people—even most practitioners and academics—think.”

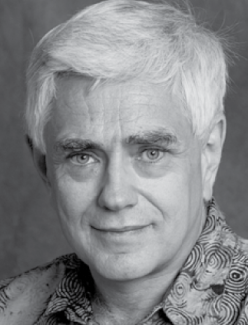

Todd Sunhwae Kim was sworn in as assistant attorney general of the division on July 28, 2021. Just shy a week of his first full year, I spoke with him over video call to hear his reflections on his team’s upcoming priorities, and learn more about the division’s vital work.

Through my Zoom portal, Kim’s office radiated with rich mahogany, a large U.S. flag hanging prominently on the back wall. He speaks with a swift and measured cadence, using almost no fillers—perhaps reflecting the many hours he has spent litigating before judges.

“I certainly think for the layperson, the work of the Environmental Protection Agency is understood and remembered more than the work of ENRD,” Kim admits. One reason may be the sheer breadth of the division’s work. ENRD encompasses 10 sections, working on well-known appellate cases, environmental crimes, defense, and enforcement—but also Indian resources, land acquisition, and wildlife and marine resources. The division’s top five clients are EPA and the departments of Interior, Agriculture, Defense, and Transportation. Yet what exactly ENRD does for these federal agencies is not straightforward.

“What I imagine most people think of when they think about environmental lawyers at the Department of Justice is environmental enforcement,” Kim says. That means attorneys bringing cases against those who violate the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, and other statutes—typically through the division’s environmental enforcement section in civil cases, or through the environmental crimes section in criminal matters.

“And they wouldn’t be wrong,” he says. “Our environmental enforcement section is one of the largest litigating sections in the whole Department of Justice.” The division’s website notes that almost half of ENRD lawyers bring cases against polluters. But as for the rest, “The defensive work we do is not as well understood.”

Lawyers at the division also defend against challenges to statutes and federal agency actions, many of which have significant implications for climate and other policy issues. Policies defended by ENRD relate to siting renewable energy projects, ensuring healthy forests, regulating proper use of public lands, establishing national monuments, and much more. The landmark West Virginia v. EPA climate case this last Supreme Court term serves as just one example of the team’s critical defensive work. The Court retained EPA’s authority to regulate carbon under a provision of the CAA but held that the agency could not use “generation-shifting”—phasing out coal—to set emissions targets.

Attorneys also work to protect rights and resources of tribes in the Indian resources section. Their cases include decades-long water rights adjudications and other complex natural resource matters. The work is “foundational, and speaks to good government and what it means to be a trustee for Indian tribes and their members,” Kim says.

ENRD also tackles worker safety violations in its environmental crime section, using criminal law to “ensure appropriate deterrence so that America’s workers are not subjected to illegal and improper conditions,” Kim says. The division even works on animal welfare. A July enforcement action against a facility owned by the company Envigo RMS in Cumberland, Virginia, resulted in the rescue of thousands of beagles that had been housed in illegal and inhumane conditions.

But despite the seemingly disparate subjects handled by the division, many cases do not fit neatly in one box. In a single case, “The environmental defense section could be dealing with a Clean Water Act issue, while the wildlife and marine resources section deals with an Endangered Species Act issue, while the Natural Resources section tackles a National Environmental Policy Act issue,” Kim explains.

The division’s sections are corded together by a team of five deputy assistant attorneys general, who each lead two sections and coordinate among each other. Put together, ENRD takes on a staggering 6,000 pending matters at a time, according to Kim. These include cases, referred matters, and other work that does not show up in court. For example, the division’s law and policy section comments on other agencies’ draft rules and helps with potential legislation and amicus briefs.

Like his division, there’s more to the assistant attorney general than meets the eye. Kim’s legal career actually began in the division he leads today, as a lawyer in the Attorney General’s Honors Program. In 2004, just six years into his work at ENRD, Kim sat opposite celebrity host Regis Philbin and won $500,000 on the premier of “Who Wants to Be a Super Millionaire?” He is also a lover of music, having grown up playing the violin and piano. In later years he sang with the Choral Arts Society of Washington—“as part of a chorus, not a soloist. No one wants to hear me solo,” he jokes.

Kim discovered a passion for the environment at a young age. “When I was 11 years old, my parents piled me and my sister into an RV, and we took a classic RV trip out to the American West to see some national parks: Yellowstone, Grand Teton, Arches, Mesa Verde,” he recounts. “I think we were only gone for two or three weeks, but it felt like months. The beauty and the grandeur, getting to do things like fish, hike—it was amazing. I think that was a big part of why I became so interested in preserving America’s beauty.”

He soon identified law as a natural avenue to channel his enthusiasm. “I grew up a pretty idealistic kid. A lot of that had to do with my parents—they immigrated to the States in the 1960s and they were full of admiration for American people and American ideals,” he says. “From a very early age, a career as a lawyer appealed to me as a way to strive for social justice.”

But he quips that “I also had an elementary school teacher who said that I was really good at arguing. So maybe that had something to do with it too.”

Not much has changed about Kim’s outlook since his childhood in New Jersey. “I’m still quite idealistic, frankly,” Kim says. “I’m proud to work at the Department of Justice, where securing equal justice under law is our mission.”

Upon graduating from Harvard Law School, he clerked for Judith Rogers of the D.C. Circuit Court. He then joined ENRD and stayed at the division for seven and a half years. The experience was “a dream beginning to my career,” Kim says today. As a young lawyer, he flew across the country to argue in all the courts of appeal, arguing memorable cases including United States v. Shell Oil Company in 2002. The case dealt with the McColl Superfund site in Fullerton, California, concerning who would bear responsibility for over a hundred million dollars in cleanup costs. “Being able to take a fairly voluminous record, master it, and then get a favorable decision on a case of great import—both financially, but also for the people affected by the Superfund site—was especially meaningful to me,” says Kim. “It really cemented my inclination to be a public interest lawyer.”

After making his rounds through the courts, Kim then became the first solicitor general for the District of Columbia. For over eleven years, he represented the district in high-level cases, including at the Supreme Court. A brief stint in the private sector later, Kim returned to the federal government as deputy general counsel for litigation, regulation, and enforcement at the Department of Energy.

Kim's first year heading ENRD has been a busy one. In May, Attorney General Merrick Garland announced a new comprehensive environmental justice enforcement strategy and launched the department-wide Office of Environmental Justice, consistent with directives outlined in an executive order by the Biden administration.

The new Office of Environmental Justice, situated within ENRD, aims to streamline and support DOJ’s work on EJ matters. As Kim puts it, “Part of the goal is just making sure that everyone keeps front of mind that environmental justice is a key aspect of DOJ’s mission.” That means “creating habits, processes, and ways of doing work that lend themselves to people centering environmental justice, now and going forward.”

EJ issues, which occur in many different contexts and potentially implicate many different statutes, “demand coordination across different components of the department,” Kim says. On the ground, that means DOJ needs to “establish a protocol for talking amongst ourselves to use all the tools we can to alleviate the burdens a community is facing.”

“These burdens may not be strictly limited to issues under the Superfund law, for instance,” he explains. “As an example, we are developing resources so that when the civil rights division has a particular matter that could implicate statutes ENRD enforces, they know that they can bring us in—and vice versa.”

Kim emphasizes that these strategies should not only maximize effective coordination, but also lead to DOJ initiating more EJ-related cases. In fact, the department’s comprehensive enforcement strategy lists as its first principle, prioritizing “cases that will reduce public health and environmental harms to overburdened and underserved communities.”

The Office of Environmental Justice is still in the process of hiring staff. But Kim notes encouraging progress already. “According to the comprehensive environmental justice enforcement strategy, every U.S. Attorney’s office is supposed to appoint an environmental justice coordinator within their district. And I’m glad to say every single one has; we have a hundred percent compliance.” The team is now moving ahead to conduct trainings and provide other resources to districts, with an eye toward ensuring lasting change in DOJ’s work to remedy burdens on low-income communities, communities of color, and Indigenous communities.

Throughout our conversation, Kim was quick to praise his colleagues, frequently expressing appreciation for their work. It was, in real time, a chance for me to observe the top guiding principle in his work: respect. When interacting with colleagues and clients, as well as opposing counsel and the courts, Kim emphasizes the importance of “working with integrity,” as he puts it. “Work with empathy, and work with an understanding of where they’re coming from. If you do those things, and you do it with competence, then good things will happen.”

The value is deeply tied to his commitment to public service, illustrated by a legal career almost entirely spent in government. “Meaning in my professional life is derived from doing things for others. Being able to do that with the talented, dedicated, and mission-driven people at ENRD makes it easy to be motivated every day—even the hard days,” he says.

Having climbed the ranks, Kim now directs this energy in leadership. Upon assuming his posts as D.C. solicitor general and as ENRD’s assistant attorney general, “One of the first things I did was sit down with every single person I’d be supervising and ask what I could do to help them be effective in their positions,” he says. To Kim, conveying respect as a leader requires “taking actions consistent with an understanding that they know their job better than I do.”

It’s no wonder that he names staff morale as one of his team’s biggest accomplishments this year. In the Partnership for Public Service’s 2021 Best Places to Work in the Federal Government, an annual list viewed as a benchmark for federal workplace satisfaction, ENRD landed within the top 10 percent. The boost is especially significant given recent political scandals at the division—the preceding head of ENRD, Jeffrey Clark, faced allegations of pursuing claims of election fraud following the 2020 presidential election. While reluctant to compare directly between administrations, Kim was forthright in sharing his team’s efforts to lift morale.

“My chief of staff, Mike Martinez, and I work hard to try to ensure that morale is high, because for the mission of the division to be accomplished as well as it can be, it’s all about the staff,” Kim says. In addition to an open-door policy for feedback, the team has reinvigorated a speaker series, inviting luminaries within and outside the government to speak to staff on relevant law and policy topics.

Looking toward the next year and beyond, Kim names combating the climate crisis and advancing environmental justice as his biggest priorities, both personally and in alignment with the Biden administration’s objectives. The Office of Environmental Justice and comprehensive EJ enforcement strategy, in particular, will require substantial attention. “I want to make sure those get off the ground and succeed, and become integrated into the department’s DNA,” Kim says.

And true to his leadership philosophy, Kim names supporting a healthy career staff as an equally important goal. “The attorneys and professional staff we have—they’re excellent. I want to keep them, and I want to motivate them to keep on doing a great job.” TEF

PROFILE For federal actions on climate change and environmental justice to succeed, the government needs a robust team of lawyers to back it up. Todd Kim, the Justice Department’s top defender of public health and natural resources, takes the lead.