On May 25 the Supreme Court, ruling in Sackett v. EPA, sharply limited the scope of the federal Clean Water Act’s protection for the nation’s waters. The Court redefined the Act’s coverage of “waters of the United States” (WOTUS), which has been hotly contested since the Court’s previous 2006 decision in Rapanos v. United States. For nearly 50 years, the Environmental Law Institute has prepared authoritative research and analysis on federal, state, and tribal wetlands and water laws, and hosted workshops focused on legal and programmatic means for wetlands protection. In this post, we’ve compiled our observations of the Sackett decision and collected materials from ELI experts to help support states, tribes, and policymakers in this new legal context.

The Decision

Echoing Justice Scalia’s plurality opinion in Rapanos, Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion for a 5-member majority (himself, Chief Justice Roberts, Justice Thomas, Justice Gorsuch, and Justice Barrett) states that the Act extends protection only to those waters that are described “in ordinary parlance” as “streams, oceans, rivers, and lakes,” and to wetlands only if those wetlands have a “continuous surface connection” to such waters “making it difficult to determine where the water ends and the wetland begins.” This decision removes protection from many wetlands that have been covered under the Act for almost a half century by both Republican and Democratic administrations. The new majority gave no deference to these administrative determinations (nor previous Court interpretations).

Justice Brett Kavanaugh (writing for himself, Justice Kagan, Justice Sotomayor, and Justice Jackson) objected that the Court majority had substituted its judgment for that of Congress. The 1977 Amendments to the Act had explicitly required that its protections extend to “adjacent wetlands,” which have included numerous wetlands with no continuous surface connection to open waters – including wetlands “separated from covered waters by man-made dikes or barriers, natural river berms, beach dunes, or the like,” as implemented thereafter by 8 different Presidential administrations. Kavanaugh writes:

The Court’s “continuous surface connection” test disregards the ordinary meaning of “adjacent.” The Court’s mistake is straightforward: The Court essentially reads “adjacent” to mean “adjoining.” As a result, the Court excludes wetlands that the text of the Clean Water Act covers—and that the Act since 1977 has always been interpreted to cover.

In rendering judgment unanimously for the Sacketts, none of the nine justices applied the Clean Water Act test devised by former Justice Kennedy in Rapanos. That test, which lower courts had treated as controlling and which provides the basis for the Biden Administration’s rule, provided for jurisdiction over waters and wetlands that have a “significant nexus” to traditionally navigable waters if they “either alone or in combination with similarly situated lands in the region, significantly affect the chemical, physical and biological integrity of” such waters.

The Consequences

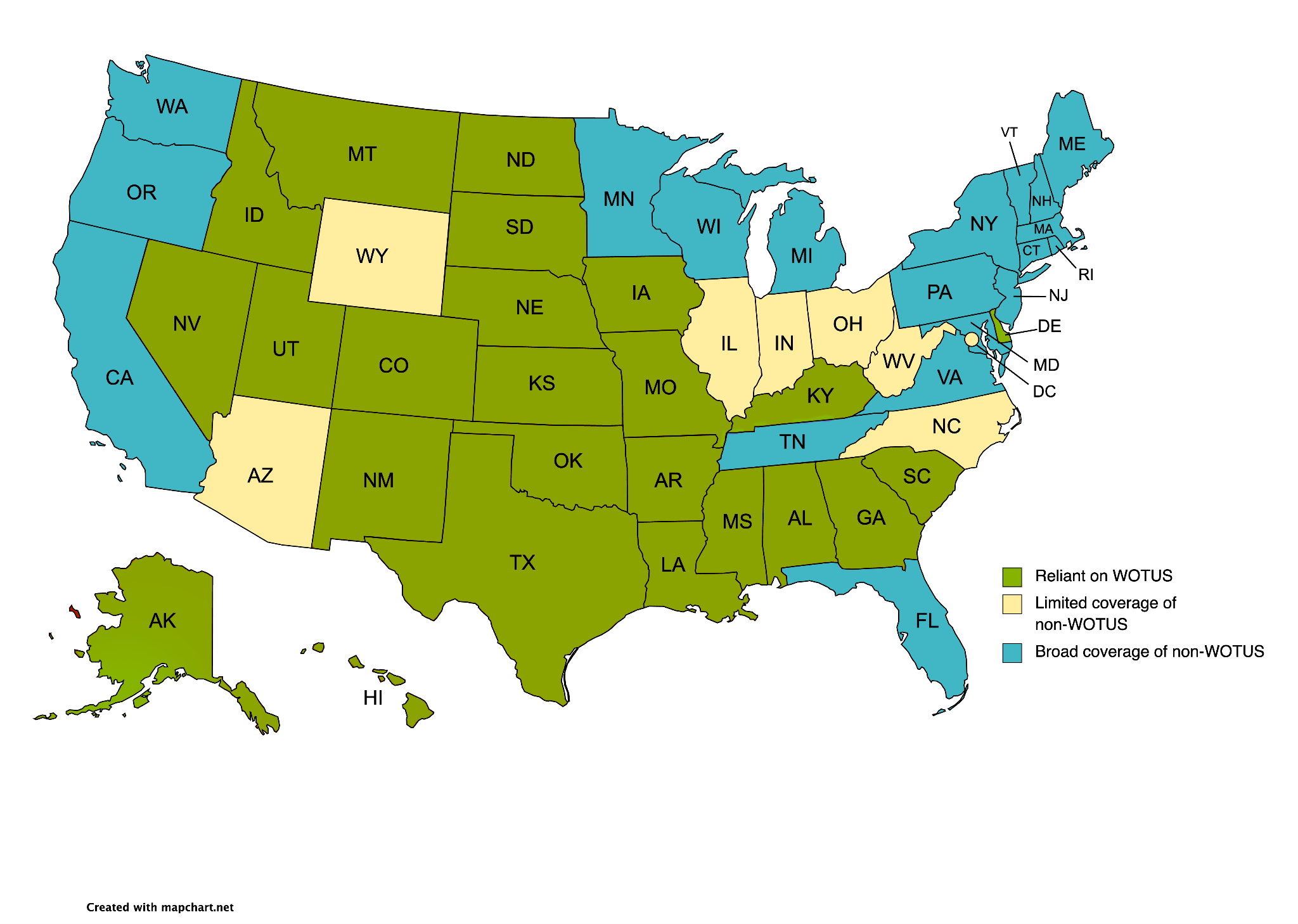

First, the Court’s decision means that immediately, numerous freshwater wetlands, bogs, fens, brackish wetlands, interdunal wetlands, floodplain wetlands cut off from rivers by levees and berms, as well as playa lakes, and complexes of prairie wetlands will no longer be subject to federal Clean Water Act permitting and protection. These waters will be protected from discharges of pollutants (including dredge and fill material) only if state laws independently impose regulatory requirements.

Table: State Wetlands/Waters Protection Laws

The Environmental Law Institute has reviewed these state laws and determined that 24 states rely entirely on the federal Clean Water Act for protection of these waters and do not independently protect them. (These are Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, and Utah).

Nineteen states have state laws protecting many of these waters, while 7 others have laws protecting at least some of the waters losing protection as a result of the Supreme Court’s action. However, even some of these states may experience gaps in coverage. For example, some (such as New York) protect only wetlands over a certain size. Others (e.g., Ohio) have adopted laws that protect isolated wetlands but do not protect wetlands that are adjacent to navigable waters but have no “continuous surface connection.”

There will need to be legislative action if protections are to be restored. But many state legislatures are not in session, or meet only in alternate years or for specific purposes. Moreover, understanding the scale of the gaps to be filled and organizing a legislative response may well take time. In the meantime, activities such as mining, development, dredge and fill, and even discharges of other pollutants may ramp up (or commence in advance of any legislative responses).

Second, the abrogation of federal regulation of wetlands without a continuous surface connection to other covered waters means that no CWA Section 404 permits will be needed for activities in these waters. This will frequently remove the only federal “hook” for the application of environmental impact review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and the requirement for federal agency consultation under the Endangered Species Act, for actions such as road-building and construction of transmission corridors.

Third, the status of intermittent streams, and other waters that are tributaries of traditionally navigable waters, remains highly unclear. The Sacketts won their case, but the Court’s decision spoke only directly to wetlands, while suggesting a very narrow view of the protection of other waters. (Indeed, in a concurrence Justice Thomas, with Justice Gorsuch, suggested that a centuries-old strict navigation test might be most consistent with his understanding of the Act and its antecedents – including the possibility that the only pollutants of legitimate federal concern might be those posing a hazard to commercial navigation).

Fourth, the nation’s water managers and residents will need to determine how to deal with levees, seasonally flooded floodplain wetlands, interdunal wetlands, and many other bodies of water with substantial hydrological connections to the nation’s waters but without continuous surface connection. This will present a huge management and conservation challenge – and may well threaten water quality, habitat, risk management, and even public health.

In his concurrence, Justice Kavanaugh observed: “For example, the Mississippi River features an extensive levee system to prevent flooding. Under the Court’s “continuous surface connection” test, the presence of those levees (the equivalent of a dike) would seemingly preclude Clean Water Act coverage of adjacent wetlands on the other side of the levees, even though the adjacent wetlands are often an important part of the flood-control project.”

Fifth, the decision will undoubtedly affect the nation’s multi-billion-dollar compensatory mitigation industry and the governments and developers that rely on its expertise and activities. Substantial investments have been made in constructing and restoring freshwater wetlands across the nation to offset permitted impacts to such wetlands under the Clean Water Act. Now, at a stroke, the permit requirement (along with the need for compensation) is gone for large areas of the country. What will be the response? Among other questions will be how to assess and coordinate remaining state mitigation requirements with a suddenly absent Corps of Engineers permitting component.

Sixth and finally, certain aspects of the Sackett decision bode ill for other federal regulatory and legislative action when reviewed by the federal courts. The Supreme Court majority gave no deference to longstanding regulatory action in implementing the Clean Water Act, citing among other things dictionary definitions and “background principles of construction.” Alluding to possible constitutional concerns, it stated that Congress must use “exceedingly clear language” in order to “alter the balance between federal and state power and the power of the government over private property,” and further, that “regulation of land and water use” lies at the “core of traditional state authority.” In her separate opinion concurring in the judgment, Justice Kagan called this “a judicially manufactured clear-statement rule,” putting a “thumb on the scales.” Such rules of interpretation will likely proliferate in their application to other laws and other regulations.

ELI Resources

- State Protection of Nonfederal Waters: Turbidity Continues (article)

- Filling the Gaps (research paper)

- Improving Compensatory Mitigation Project Review (research paper)

- Developing Wetland Restoration Priorities for Climate Risk Reduction and Resilience in the MARCO Region (research paper)

- Sustaining Coastal Wetlands in a Time of Severe Storms and Rising Seas (webinar recording)

- Bridging Remote Sensing, Participatory Science, and Wetlands Programs: An ELI Workshop (webinar recording)

- Community Engagement for the Protection of Wetlands: National Wetlands Awards (webinar recording)