How we communicate about our environment matters just as much as what we communicate if we want our message to be heard. ELI Press’ new book, Mud Lake, reaches out to a broad audience, from middle schoolers to senior citizens, by incorporating illustrations and universal adventure stories of how kids engaged with natural areas during the 1960s. The book is filled with narrations about sights, sounds, feelings, and smells that spark fond memories for anyone who may have experienced similar landscapes during their youth. Colorful sketches and simplistic diagrams accompany the text to further reel in reader’s attention.

For example, to the right we see Beth Hagenbuch, one of the books "characters," as she investigates the edge of a small pond in the Woods near Mud Lake. She aspired to keep up with her older brother but was equally content to explore on her own, squatting at the pool’s edge, prodding the murky water, navigating her steps along the pond’s perimeter, examining small things in the leaf litter, or making her own way over and under fallen logs and branches through the Woods.

Easy-to-understand scientific narrations are woven into the adventure stories, expressing factual explanations about our environment and its importance for us all. And instead of simple sound bites about climate change causing the more frequent and intense storms that we are experiencing, as most people hear on TV news, Mud Lake provides the basic science behind why climate change is happening and solutions to address it.

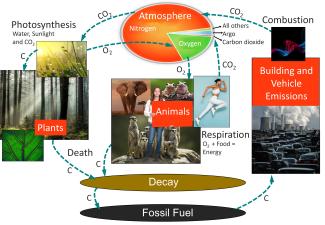

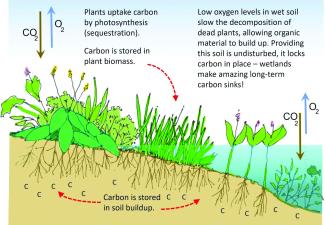

The carbon cycle is emphasized as a life support circle that balanced the trade of carbon dioxide (CO2) between plants and animals for millions of years. The book explains how it starts with photosynthesis—a process green plants use to create biomass from CO2, water, and sunlight. CO2 is broken apart, trapping carbon within plants as they grow, which builds the definition for a “carbon sink”, and the leftover oxygen is released into the atmosphere. Further narration explains how people and critters use the oxygen when combining it with their ingested plant-based food to fuel life-sustaining activities like movement and digestion. This process, known as respiration, “oxidizes” the carbon in their food gained from plants. As this happens, energy is released into animals’ bodies allowing them to function, and newly formed CO2 is outbreathed into the atmosphere where it can return to the plant world. So goes the carbon trade. As plants and animals die, carbon stored in their biomass neatly becomes part of the earth.

Movements caused by “circular energy” are also investigated, including large cosmic circles like the earth revolving around the sun and the moon around the earth. Natural circles on earth, including the water cycle and the circle of life itself, are discussed in casual, entertaining language.

In a more abstract discussion, “social circles” linking family and friends are identified as building blocks for communities, which are fundamental to human survival. Understanding this concept is a primer for a chapter devoted to social injustice. But regardless of whether these circles are physical movements or socially connected loops, unused materials or disruptions like racism leading to their breakage are called out as “waste”. In determining what ingredients give rise to “sustainability,” large, simplistic moves occurring in nature, which don’t emit waste, offer good examples of what works.

The book further drills down on wetland science, explaining how many wetlands evolved from glacial lake basins that are now filling in due to “eutrophication.” The book explains how this process can wander in one of two separate directions, depending on soil acidity, resulting in a bog or marsh, having two distinctly different plant communities. Phosphorus is known to accelerate the process, and humans have wastefully let this element invade many waterbodies, prematurely degrading them for recreational purposes. Worse yet, bogs have become targets for peat mining—another source of carbon fuel, which further overloads our atmosphere with CO2 when catching on fire. Mud Lake also illustrates wetlands' importance as carbon sinks when undisturbed.

Doors are cracked along the way, giving opportunities for deeper thought about natural areas, from a spiritual perspective, and how these landscapes go well beyond providing mechanisms to balance the carbon budget. In the end, climate plans are emphasized as blueprints to mitigate and adapt to our changing world, both to bring down the temperature and preserve biodiversity. Mud Lake makes it clear that natural landscapes need to be preserved not only because of their importance in balancing the carbon budget but for the sanctuary they provide for wildlife and human well-being.