Vibrant Environment

Pollution Control

All | Biodiversity | Climate Change and Sustainability | Environmental Justice | Governance and Rule of Law | Land Use and Natural Resources | Oceans and Coasts | Pollution Control

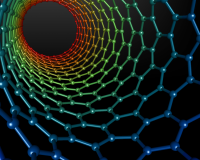

Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, coal-fired systems have been emitting a pollutant we did not even know existed . . . until now. In 2014, a team of scientists studying arsenic in the Dan River coal ash spill site in North Carolina discovered a new nano-scale version of titanium oxides that had never been seen before.* What they discovered were titanium suboxides, or so-called Magnéli phases, which were first synthesized in the 1930s. These substances are extremely rare in nature, seen only in rocks having an extraterrestrial origin (meteorites, lunar rocks, and interplanetary dust particles), and at one known point on the earth’s surface—rock formations on the central coast of western Greenland.

For months, Volkswagen has been reeling from an emissions manipulation scandal affecting over one-half million U.S. vehicles and costing the company more than $20 billion in reparations. The financial and reputational damage has now invaded the VW supply chain, with Bosch, the company who developed the emissions control programs for VW, agreeing to pay customers over $300 million in damages. Who is next? Probably Fiat/Chrysler and Daimler, both under investigation for evading diesel emissions rules.

In a series of executive orders, the president has requested that agencies review several environmental protection rules, and if deemed necessary, repeal or modify rules to better facilitate economic growth. One such rule, the Clean Water rule, also known as the Waters of the U.S. rule (WOTUS), has been in the crosshairs of industry for some time.

I was in the 10th grade when I first heard about the ecological and human health disaster caused by petroleum extraction in Ecuador. A film festival in my hometown showed Crude, a documentary that details the impact of abandoned oil fields near Lago Agrio and the accompanying legal battle. Local populations whose livelihoods and health were allegedly harmed by careless corporate and government actions had been fighting to hold Texaco accountable for cleanup and compensation since 1993. The film, however, focused on several key characters that became involved in the case many years later. There were lawyers (Steven Donzigner and Pablo Fajardo), a corporation (Chevron, which acquired Texaco in 2001), celebrities (including Sting), and a young and charismatic Presidente (Rafael Correa of Ecuador).

The last thing the push for TSCA reform needs is another delay, and Senator Paul's unexpected interest in H.R. 2576 has caused just that. Under typical circumstances, a Member's focused interest in legislation is refreshing, and as today highlights, entirely too infrequent. In this instance, the circuitous road to TSCA reform is anything but typical—the complexity of the legislation has invited an unusual divisiveness that has frustrated passage—and delay is the enemy of the good.

Timing is everything. Last week, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill, the Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act, updating and reforming the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), which hasn’t been revised since its passage in 1976. The overwhelming vote (403–12) reflected the fact that the chemical industry, much of the environment community, and most other interested parties have agreed on the need for such reform for years, if not decades.

ELI was founded in 1969—a time when U.S. environmental law was in its infancy and needed a place for cultivation and growth (an imperative that is still incredibly relevant today given the interconnectedness and severity of conservation challenges across the globe). At that moment in time, individuals across the country looked around and saw rivers catching on fire, poor air quality making it hard for children to breathe, and unfettered toxic pollution.