I was introduced to mangroves early in my childhood during family trips to Bear Cut in Key Biscayne, Florida—the same plants that grew in my family’s hometown on the northern coast of Cuba. In 2003, I first used mangrove imagery in my artwork as a metaphor for the immigrant. I imagined the mangrove propagules floating along the water and setting root on a sandbar. Little by little they would grow alongside each other, capture sediment, create land, and build new habitats. Like immigrants in a community who come together to support one another, the roots of each mangrove tree come together to create a formidable structure that protects against the dangers of storm surge.

Expanding on this idea, mangrove seedlings were central in the creation of my Miami Mangrove Forest in 2004, a public art project that saw 800 volunteers paint murals of mangrove seedlings on 56 columns underneath Miami’s highways as a metaphoric reforestation. After growing increasingly concerned about our changing climate, my perspectives on tackling environmental issues began to shift from that of a traditional artist who depicts an issue to that of a social practitioner who attempts to solve it.

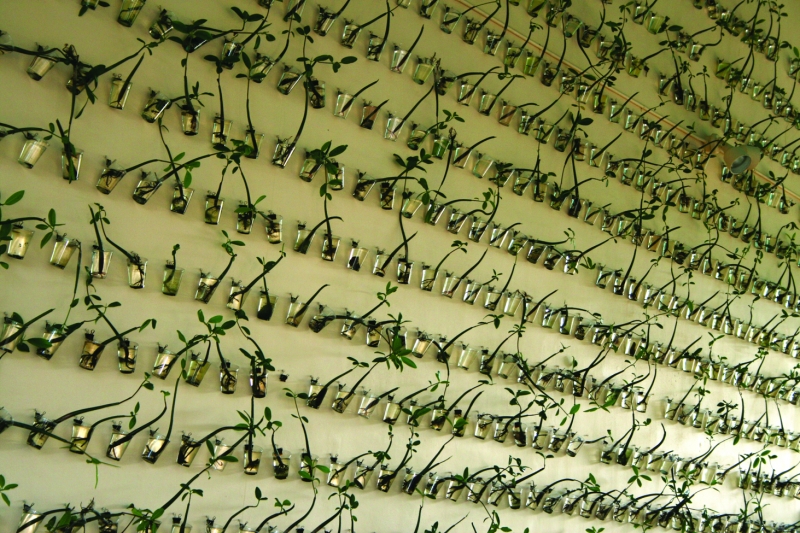

Launched in 2006, my Reclamation Project aimed to engage people in rebuilding ecosystems above and below the waterline, but more importantly, to transform those participants into eco-emissaries who understood and embraced environmental stewardship. Together, they collected mangrove propagules and displayed them as vertical nurseries on Miami Beach retail spaces where mangroves once grew. These individuals did more than create public art installations—they advanced an educational campaign about the importance of wetlands, and then planted the installation’s mangroves in the areas of Biscayne Bay that had not yet been barricaded by concrete seawalls. This project significantly influenced the direction and methodology of my greater social practice, serving as a point of departure that ushered in a process of community engagement and institutional infiltration that has continued to evolve over the years.

Launched in 2006, my Reclamation Project aimed to engage people in rebuilding ecosystems above and below the waterline, but more importantly, to transform those participants into eco-emissaries who understood and embraced environmental stewardship. Together, they collected mangrove propagules and displayed them as vertical nurseries on Miami Beach retail spaces where mangroves once grew. These individuals did more than create public art installations—they advanced an educational campaign about the importance of wetlands, and then planted the installation’s mangroves in the areas of Biscayne Bay that had not yet been barricaded by concrete seawalls. This project significantly influenced the direction and methodology of my greater social practice, serving as a point of departure that ushered in a process of community engagement and institutional infiltration that has continued to evolve over the years.

This evolution of my practice coincided with an increased understanding of our climate emergency and one  particular realization about Miami: we are dealing with a wicked problem. As oceans rise and the reality of climate change finds clarity in the psychology of Miami’s real estate markets and tourism economy, many marginalized members of the community are going to suffer more than those who have power and means. Sea-level rise will disproportionately impact people of color and poorer residents in low-lying areas (as low-income neighborhoods are abandoned, property owners will lose everything) and those who rent in higher-lying low-income neighborhoods (evicted renters—the victims of climate gentrification). Miami’s sea-level rise issues demand creative approaches to obtaining political accountability, economic justice, and a transition to an inclusive, clean economy.

particular realization about Miami: we are dealing with a wicked problem. As oceans rise and the reality of climate change finds clarity in the psychology of Miami’s real estate markets and tourism economy, many marginalized members of the community are going to suffer more than those who have power and means. Sea-level rise will disproportionately impact people of color and poorer residents in low-lying areas (as low-income neighborhoods are abandoned, property owners will lose everything) and those who rent in higher-lying low-income neighborhoods (evicted renters—the victims of climate gentrification). Miami’s sea-level rise issues demand creative approaches to obtaining political accountability, economic justice, and a transition to an inclusive, clean economy.

Building upon the knowledge and relationships developed during the creation of the Reclamation Project and subsequent participatory eco-art projects such as Native Flags, FLOR500, and the Underwater HOA, I started a campaign to engage residents at every corner of Miami-Dade County in a project designed to educate and mobilize participants around the climate crisis. Plan(T) is a participatory eco-art project aimed at helping South Florida residents learn about and plan for a future impacted by climate change, sea-level rise, and saltwater intrusion. Through a combination of installations, presentations, and outreach events, community members are encouraged to plant a red mangrove propagule alongside a white flag (denoting their property’s elevation above sea level) in their front yards. This process advances the project’s goals of educating a broad audience about and preparing them for the consequences of a rapidly changing climate by catalyzing conversations with family and friends, helping sequester carbon dioxide, and growing the local salt-tolerant native tree canopy that will survive saltwater intrusion. Conceptually, the mangrove tree functions as a visualization of the growing problem. As the tree is nurtured and grows, so does the vulnerability of the area it resides in, the beauty of the tree juxtaposed with what its growth represents. The mangrove also lends itself as a subversive quality in this project, as once the mangrove is planted, it is illegal under Florida law to remove it, an allusion to the permanence of the issue at hand.

Building upon the knowledge and relationships developed during the creation of the Reclamation Project and subsequent participatory eco-art projects such as Native Flags, FLOR500, and the Underwater HOA, I started a campaign to engage residents at every corner of Miami-Dade County in a project designed to educate and mobilize participants around the climate crisis. Plan(T) is a participatory eco-art project aimed at helping South Florida residents learn about and plan for a future impacted by climate change, sea-level rise, and saltwater intrusion. Through a combination of installations, presentations, and outreach events, community members are encouraged to plant a red mangrove propagule alongside a white flag (denoting their property’s elevation above sea level) in their front yards. This process advances the project’s goals of educating a broad audience about and preparing them for the consequences of a rapidly changing climate by catalyzing conversations with family and friends, helping sequester carbon dioxide, and growing the local salt-tolerant native tree canopy that will survive saltwater intrusion. Conceptually, the mangrove tree functions as a visualization of the growing problem. As the tree is nurtured and grows, so does the vulnerability of the area it resides in, the beauty of the tree juxtaposed with what its growth represents. The mangrove also lends itself as a subversive quality in this project, as once the mangrove is planted, it is illegal under Florida law to remove it, an allusion to the permanence of the issue at hand.

Fifteen years ago, I created a platform that inspired participants as protagonists and stewards. Today, we understand that many of the mangroves they planted will succumb to rising seas. The next 15 years will be harder than the last 15. Although it is difficult to imagine or accept the catastrophic effects of climate change on our community, we must continue to work together and learn together to problem-solve. Socially engaged art can lead the way.