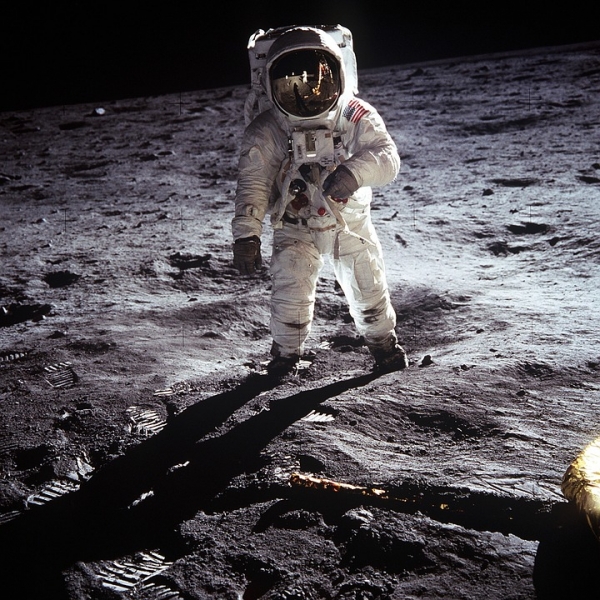

In a period of less than a month, everything good seemed possible for America. First came the Moon landing, on July 20, 1969. Billions watched our astronauts live from the lunar surface and took pride in humanity’s achievement. In the United States, the concept of collective will to conquer a huge national challenge got a big boost. Project Apollo joined the Manhattan Project as paradigms of government-led Yankee ingenuity licking a technological problem — and on a tight timetable to boot, expenses be damned because of the extreme nature of the threat.

Then, on August 15, “half a million strong,” in Joni Mitchell’s lyric, gathered for the Woodstock Music & Arts Fair, a mega-event never previously attempted and never duplicated in the half century since for its sense of common destiny and generational purpose. In covering her tune a few months later, Crosby Stills & Nash riffed a rejoinder that shows the synchronicity between Apollo and Woodstock: “We are stardust, we are golden. We are billion-year- old carbon. And we got to get ourselves back to the garden.”

Years later, Mitchell observed that at the 1969 festival, the kids “saw that they were part of a greater organism.” Indeed, by the time the voting age came down to 18 months later, the Boomers had established themselves as a political force. And while the war in Vietnam continued to divide the country, the can-do spirit of collective action for common good embodied in Project Apollo and Woodstock Nation found a favored outlet with back-to-the-garden environmental lawmaking.

Years later, Mitchell observed that at the 1969 festival, the kids “saw that they were part of a greater organism.” Indeed, by the time the voting age came down to 18 months later, the Boomers had established themselves as a political force. And while the war in Vietnam continued to divide the country, the can-do spirit of collective action for common good embodied in Project Apollo and Woodstock Nation found a favored outlet with back-to-the-garden environmental lawmaking.

Exploring the Moon “has altered our view of Earth, its ecosystems, and the evolution of a habitable world,” according to David Kring, a geologist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute. “Earth Day’s origins can be traced to the Apollo missions. It is only fitting to recognize the significant contributions lunar exploration has made to better understand planet Earth.”

Analysis of the rocks returned by astronauts as well as photographs of the cratered surface made from orbit led scientists to create the impact theory of extinction on Earth, and even to postulate that the conditions for our biosphere arising in the first place on what was a barren planet were the result of constant hits by large celestial bodies.

Indeed, the lunar rocks proved that Earth’s water, critical to life, was not present on our globe originally but was the later gift of billions of colliding comets, composed of ice and dust, over the eons. The human body is 60 percent comet water and some comet carbon as well, and most of the remaining elements were produced in the center of supernovae near the dawn of the universe. We are indeed, as the astronauts helped prove, made up of stardust and billion-year-old carbon.

Apollo’s greatest gift to human understanding of the Earth’s environment would come three years after the initial landing, when the voyagers returning from the final lunar mission took the first photograph giving a view of our species’ home planet in full phase. The “Big Blue Marble” picture, azure seas and green-brown continents beneath swirling white clouds, went viral, maybe the first such image to do so, appearing on book covers and tote bags with a message that maintaining “the ecology” on Spaceship Earth is like ensuring breathable air is for astronauts.

Meanwhile, back at the time of Apollo 11 and Woodstock, legislators were drafting a law making it the policy of the United States to support Mitchell’s garden, our planetary life-support system, for future generations. “I have come to lose the smog,” she sang, “and I feel myself a cog in somethin’ turning.”

Indeed, in those few weeks in the summer of 1969, it became “the time of man” for all that is harmful about our species’ impact to “turn into butterflies across our nation.”

[This piece originally appeared in the July – August 2019 issue of The Environmental Forum® and is reprinted with permission]