The founders of modern conservatism saw a role for the state in ensuring environmental quality by regulating polluters. While that changed in more recent decades, there are signs that a new generation of conservatives favors a governmental role in reducing emissions.

Daniel A. Farber is the Sho Sato Professor of Law and codirector of the Center for Law, Energy, and the Environment at the University of California, Berkeley.

Daniel A. Farber is the Sho Sato Professor of Law and codirector of the Center for Law, Energy, and the Environment at the University of California, Berkeley.

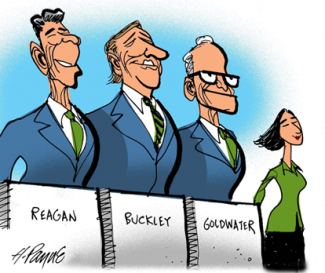

Today, conservatism is associated with anti-environmentalism. It comes as something of a shock, therefore, to discover that in the 1960s and 1970s, in the midst of establishing the modern conservative movement, iconic figures such as Ronald Reagan, Barry Goldwater, and William F. Buckley all took staunchly pro-environmental positions, including a willingness to countenance regulations that might be considered too radical for today’s Democrats. Yet today, conservatism has become associated with skepticism about environmental science, enthusiasm for expanding development activities on public lands, a firm belief in the merits of fossil fuels, and an instinctive hatred for regulation.

The process by which these pro-environmental views were forced out began in the 1980s but did not reach fruition until the conservative backlash against the Obama administration. The way was eased for these anti-regulatory views to triumph by large infusions of money from conservative business leaders, especially from the fossil fuel industries — such as the Koch family. Pro-development interests in the western states also played a role, starting with the Sagebrush Rebellion that started in the 1970s. Political and economic forces, more than logic or empirical evidence, gave anti-environmental views ascendancy among conservatives.

Despite the seeming hegemonic dominance of anti-environmentalism within the conservative movement, there are some hopeful straws in the wind. The coal industry is in seemingly irreversible decline, and the major oil companies have begun to moderate their views on environmental issues, including climate change. Meanwhile, the renewable energy sector is becoming an increasingly powerful economic and political force, even in red states such as Texas, Iowa, and Kansas. Some western states have begun to diversify their economies and no longer view mining and oil as unmitigated benefits. And a handful of conservative thinkers have started to rethink the anti-environmental verities they learned from an older generation. Indeed, just before this article was written, Congress passed a defense spending bill that calls climate change a serious threat to national security. In the House, 46 Republicans crossed the aisle to vote in favor of that provision.

Rediscovering this lost history is important because it shows that vigorous environmental protection can be consistent with strong conservative values. A revival of this school of thought could enrich discourse within the conservative movement and help heal the growing schism between conservatives and scientists. It would also begin to depolarize debates over environmental policy, helping to defuse knee-jerk reactions on both sides and move policy debates in a more constructive direction. If the signs of a conservative-environmentalist revival come to fruition, the result could be a healthier political atmosphere and a more stable, better-designed regulatory regime.

This article will follow a largely chronological path, beginning with the surprisingly pro-environmental views of the founding fathers of modern conservatism. The focus then turns to the backlash that began in the late 1970s and has carried through to the present. Finally, we will turn to examine some hopeful signs that may herald the beginning of a shift in conservative values.

Conservative thought in some form or another goes back to the ancient Greek philosophers, but modern American conservatism has more recent roots. The movement arose from William F. Buckley’s efforts to fuse three strands of conservative thinking: libertarianism, traditionalism, and anti-communism. Buckley’s podium, the National Review, remains the leading conservative journal today. Yet, even before environmental issues received attention from Congress, Buckley himself viewed environmental problems very seriously — and as prime prospects for regulation.

Buckley ran for mayor of New York in 1965 with a campaign designed to educate the public about conservative views rather than securing electoral victory. (When asked what he would do if by chance he won, Buckley quipped, “Demand a recount.”) Buckley took a strongly environmentalist position. He called pollution control “a classic example of the kind of thing that government should do . . . because the people cannot do it themselves.” He proposed that all cars sold in the city or entering the city be required to comply with California’s new, stricter air pollution standards for vehicles. In order to reduce traffic, he advocated a toll to discourage cars from entering Manhattan and an elevated bikeway for 125 blocks down Second Avenue.

Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign marked the emergence of modern conservatism on the national stage. His followers began the conservative takeover of the Republican Party and established institutional structures, rhetoric, ideology, and political strategies such as mass fundraising efforts that prevail even today. Goldwater was generally a harsh critic of federal regulation, so his views on the environment may come as something of a surprise. His 1970 book The Conscience of a Majority has a chapter entitled “Saving the Earth.” “Our job,” he said, “is to prevent that lush orb known as the Earth . . . from turning into a bleak and barren, dirty brown planet.” Continuing to paint environmental problems in stark terms, he added: “It is difficult to visualize what will be left of the Earth if our present rates of population and pollution expansion are maintained.”

Goldwater said the pollution issue “should be much more than a political football for aspiring office-holders or office-keepers.” He said, “Although I am a great believer in the free, competitive enterprise system and all that it entails, I am an even stronger believer in the right of our people to live in clean and pollution-free environments.” Thus, he said, “When pollution is found, it should be halted at the source, even if this requires stringent government action against important segments of our national economy.” He added that the American people might need “to make some unhappy and large-sized sacrifices in order to preserve their environment.” For instance, he said, it might be necessary to crack down on pollution from coal-fired power plants, and that in turn might require sharp cuts in electricity use.

Ronald Reagan, too, embraced environmentalism. In 2015, a writer in the Los Angeles Times called Reagan “the most environmental governor in California history — protecting wild rivers from dams, preserving a Sierra wilderness by blocking highway builders, creating an air resources board that led to the nation’s first auto smog controls.” This may be an overstatement, but there were indeed some major environmental achievements during his tenure. Concern about the environment was not just a political gambit for Reagan. His childhood along the Rock River in Illinois and his experiences in filming movies in the West had left him with a warm regard for nature.

One of Reagan’s accomplishments as governor was safeguarding Lake Tahoe from impacts of surrounding development. Although he had a strong preference for local control of land use, once he had seen the lake’s condition he agreed that an interstate solution was required, and he signed a compact with the governor of Nevada establishing a joint regional planning authority.

There were other examples of Reagan’s efforts to protect nature. A particularly arresting example of his environmentalism involved a dramatic horseback ride through the Sierras to stop a federal highway project. He also blocked dam proposals on the Eel River and on the Middle Fork of the Feather River. Perhaps more notably, he signed California’s wild and scenic rivers legislation. During the Reagan years, California also added 145,000 acres of land to its state park system along with areas of the Pacific Ocean. And even more notably, Reagan signed the California Environmental Quality Act, which has been a thorn in the side of development interests ever since.

Reagan also signed legislation creating the California Air Resources Board, one of the strongest state regulatory agencies in the country. During Reagan’s term as governor, CARB set air quality standards for stationary sources such as power plants and adopted the nation’s first nitric oxide standard for vehicles.

This liaison between conservatives and environmentalism was not to last. Instead, regulatory backlash increasingly dominated both the conservative movement and the Republican Party. It is important to understand the roots of this backlash and especially the role played by business interests and wealthy political donors in catalyzing the metamorphosis.

In response to the new regulatory climate, a symbiotic relationship began to emerge between anti-regulatory ideologues and parts of the business community (particularly manufacturing, mining, and oil). This alliance between business and movement conservatives — of which Reagan would become an exemplar — can be seen as early as the 1960s, when Fred Koch (father of today’s Koch brothers) ordered copies of Goldwater’s conservative manifesto, Conscience of a Conservative, for every library and newspaper in Kansas. By the time Reagan left office, the Koch family had also launched the Cato Institute, which “promoted the purest strands of libertarian thinking.”

A memo by soon-to-be-Justice Lewis Powell for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce became a manifesto for corporate resistance to regulation. Shortly before going on the bench, Powell wrote the influential memo decrying what he considered an anti-capitalist intellectual climate and calling for the chamber to finance cadres of more sympathetic scholars. The Powell memo received considerable attention from conservative elites. Although the chamber did not take action, others heeded the call to develop a counterweight to liberal academics.

The anti-regulatory movement led to the establishment of major Washington think tanks. The American Enterprise Institute had been created years earlier by the chairman of the country’s largest asbestos manufacturer, but its budget increased tenfold during the 1970s. Even more important was the Heritage Foundation, which bills itself as promoting “conservative public policies based on the principles of free enterprise, limited government, individual freedom, traditional American values, and a strong national defense.” Heritage and AEI provided key staff for the Reagan administration and later for George W. Bush and Donald Trump. Both foundations experienced surges of funding in the mid-1970s, but Heritage outdid AEI by developing a new model of politically engaged, less-academic activity.

By the late 1970s, the Republican Party had begun to move away from environmental protection. Instead, renewed stress was placed on increased resource development and introducing balance between environmental and economic values. By 1980, the change from an early embrace of environmental protection was dramatic. The Republican Platform that year blamed “excessive regulation” for “our nation’s spiraling inflation” and for stifling “private initiative, individual freedom, and state and local government autonomy.” The platform reflected both the influence of the business community and a backlash of rural interests in western states against conservation.

Reagan’s positions in the first few years of his presidency were in tune with the GOP platform and strikingly at odds with his actions as governor. But he revamped his approach when the initial anti-environmental initiatives ran into trouble. In the end, he went along with a considerable number of new protections for the environment. He accepted significant environmental legislation from Congress, toughening regulation of hazardous waste (the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act) and requiring public disclosures of the use and discharge of toxic chemicals (the Toxics Release Inventory).

On at least one major occasion during his presidency, Reagan personally championed environmental protection. He signed the Montreal Protocol to protect the ozone layer, calling it a “monumental achievement.” The president sided with EPA and the State Department on regulations to phase out ozone-destroying chemicals over the objections of cabinet members who argued for distributing hats and sunglasses as a cheaper alternative to preventing skin cancer. In his diary, he referred to the ozone protocol as “an historic agreement.”

Reagan also signed legislation addressing climate change. In 1983, EPA had warned about the risk of a runaway greenhouse effect, though others in the administration considered this alarmist. The Global Climate Protection Act of 1987 contains congressional findings about the possible risks of climate change. The law goes on to state that “necessary actions must be identified and implemented in time to protect the climate.” It calls for international agreement and requires the president to “present a coordinated national policy on global climate change” to Congress. In the House, conservative stalwart James Sensenbrenner said he “support[ed] the development of a coordinated national policy so this country can continue its effective participation with other nations to address this important issue.”

The 1987 Global Warming Act grew out of a summit between Reagan and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev earlier that year. The two leaders agreed they would “continue to promote broad international and bilateral cooperation in the increasingly important area of global climate and environmental change.” In a letter to the New York Times, the head of a scientific organization called this agreement “the best-kept secret of the Reagan-Gorbachev summit — and potentially the most portentous for global well-being during the 21st century.”

The dominant strain in current conservative thought, and in an increasingly conservative Republican Party, is vehemently anti-environmental, coupled with seemingly unbounded enthusiasm for developing public lands and fossil fuel resources. As in the 1980s, this rightward push has been supported by funding from energy interests and enthusiasm by rural western voters. Yet some of these forces may now be abating, at least a little.

There is no doubt that the interests of the fossil fuel industry still carry important weight in American politics. But part of the fossil fuel coalition has been seriously weakened by economic changes. The coal industry’s economic plight is well known. In 2016, coal production was the lowest since a major strike 35 years ago, and coal use dropped over 25 percent from the previous year. In April 2016, Peabody Coal filed for bankruptcy, joining most of the other major firms. Coal production rebounded slightly in 2017, mostly due to an uptick in exports. Economists expect continued decline in the industry, notwithstanding the efforts of the Trump administration to prop it up. Moreover, the fleet of coal-fired power plants is rapidly aging, with new generation now relying almost wholly on other energy sources such as natural gas, solar, and wind. In 2016, for the first time, more Americans were employed in clean-energy jobs than in oil and natural gas extraction or coal mining.

The oil industry, while far from showing signs of similar decline, has begun to readjust its views of climate change. The major oil companies acknowledge the reality of climate change, and many endorse the need for government action. For instance, when he was CEO of ExxonMobil, former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said that “for many years ExxonMobil has held the view that the risks of climate change are serious and do warrant action.” The energy giant’s assessment of new projects assumes that eventually it will have to pay a carbon tax or some other cost for a project’s carbon emissions.

Meanwhile, some conservatives are beginning to rethink their reflexive opposition to environmental protection. One hopeful sign can be found in the writing of “reform conservatives,” many of whom are profoundly disenchanted with the Trump administration. Newspaper opinion writers such as Ross Douthat of the New York Times and Michael Gersen and Jennifer Rubin of the Washington Post have rejected denial of climate science as an untenable conservative position. The idea of a carbon tax is also getting a serious hearing among some conservatives, such as the libertarian Niskanen Center. Indeed, Niskanen filed an amicus brief in a federal lawsuit filed by children claiming that unrestricted emissions violate the public’s property rights under the Public Trust Doctrine.

Within the legal academy, there are also some signs of change. Perhaps the most sustained effort to elaborate a new conservative environmentalism has come from a younger libertarian law professor, Jonathan Adler. Adler laments that “the dominant alternative on the political right has been reflexive — almost reactionary — opposition to anything green,” characterized by the view that “whatever the Sierra Club or Al Gore supports must be opposed.”

Indeed, he says, “This reactionary posture has expanded beyond reflexive opposition to environmental policy proposals to encompass a reflexive denial that environmental problems, of whatever sort, actually exist.” Adler endorses the polluter-pays principle, calling for emissions fees, including a carbon tax. Notably, Adler has argued that sea-level rise caused by climate change is a violation of private property rights of coastal landowners. Adler does not stand alone, as a number of younger legal scholars are beginning to rethink conservative viewpoints.

It is too soon to say whether these new voices and the changing configuration of business interests will alter the tenor of conservative environmental views. But at the very least, they do offer grounds for hope.

Today’s anti-environmental stance is not an unalterable component of conservative thought. As we’ve seen, the founding fathers of modern conservatism took a strikingly different stance in the early days of the modern environmental era. Buckley, Reagan, and Goldwater, the iconic figures of modern movement conservatism, apparently saw no contradiction between right-wing philosophies and enthusiastic support for environmental protection. Even after changing times had pushed them in the other direction, they still showed flashes of environmentalism, such as Reagan’s support of the Montreal Protocol.

Much of the pressure against environmentalism came from the fossil fuel industry and from extractive industries in the western states. Those pressures could now be abating, as the coal industry’s long-term influence declines, and the oil industry repositions itself in response to rising pressures to address climate change.

A thaw in conservative views about the environment could enrich a public discourse that has seemingly become trapped in tribalism. Liberals would benefit from more thoughtful responses, while the conservative movement would benefit from more fruitful internal debate. In short, both the right and the left have something to gain if pro-environmental views were once again more prevalent among conservatives. TEF

Daniel A. Farber is the Sho Sato Professor of Law and codirector of the Center for Law, Energy, and the Environment at the University of California, Berkeley.

Daniel A. Farber is the Sho Sato Professor of Law and codirector of the Center for Law, Energy, and the Environment at the University of California, Berkeley.