The impacts of climate change are being felt throughout all regions of the United States and are expected to worsen with every fraction of a degree of additional warming. Those were some of the headline takeaways from the Fifth National Climate Assessment (NCA5), published November 14, 2023.

Mandated by Congress in the Global Change Research Act of 1990, the National Climate Assessment is a periodically updated report prepared by the U.S. Global Change Research Program, comprised of scientists from across 14 federal agencies, to assess human-induced and natural trends in global change and to project those trends for the future. Much of the report focuses on scientific advances in climate research, providing updated analyses of climate risks in the United States from the previous version published in 2018. However, this latest iteration also contained a chapter dedicated to social systems and justice—something not seen in prior assessments.

Issues of justice arise from climate change due to the unequal distribution of its consequences on both individuals and communities—e.g., extreme heat in urban heat islands—and ability to cope with them, which also depend in part upon historical and contemporary treatment of certain groups of people. For example, redlining and predatory loan practices have made it so that low-income and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) households are often the ones that are within environmentally hazardous areas. Moreover, a myriad of economic and legal factors may prevent households from recovering from environmental events, including those made worse by climate change such as weather-related disasters. To learn more, see the Climate Justice module of the Climate Judiciary Project’s Climate Science and Law for Judges curriculum.

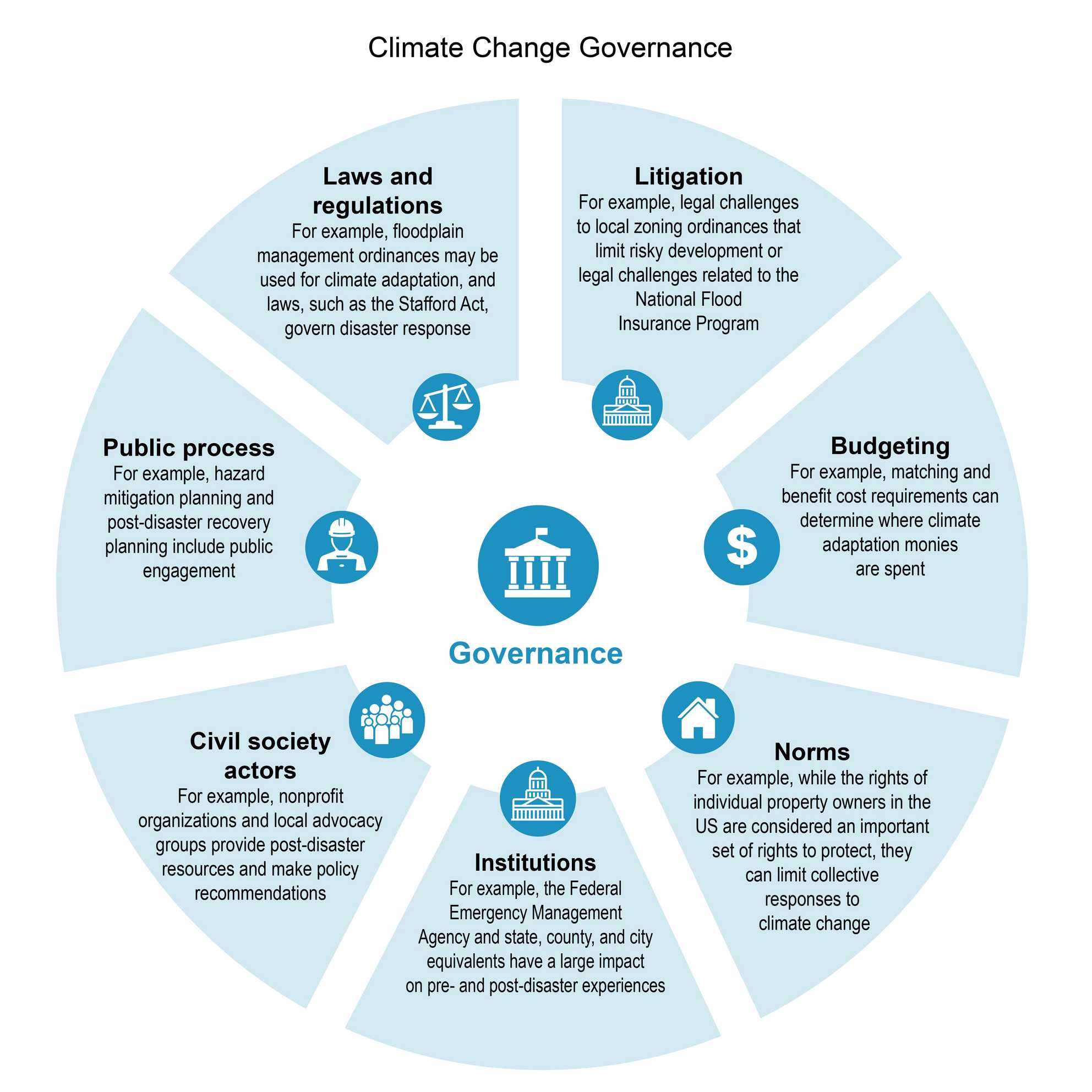

The NCA5 chapter on Social Systems and Justice defines climate justice as “the recognition of diverse values and past harms, equitable distribution of benefits and risks, and the procedural inclusion of affected communities in decision-making processes.” According to the authors, there are seven social systems that shape climate governance throughout the United States, which can be leveraged to either promote climate justice or exacerbate climate injustice. Of note, two of the seven—laws and regulations and litigation—are squarely legal, highlighting a key role for the judiciary to affect climate governance (Fig. 1). Judges play a critical role beyond these two wedges as well—especially as their actions and decisions can be key factors in shaping institutions and norm-building around climate change.

Figure 1. Social systems that shape climate governance in the United States. These systems can be leveraged to promote climate justice or exacerbate climate injustice. Brief examples of how climate justice might be encouraged are described under each system. Source: Figure 20.2 from Fifth National Climate Assessment, Ch. 20.

For climate governance to be both just and effective, communities that have been historically excluded from decision-making must be invited to take part in the conversation. Research indicates that the ways in which people learn about and understand climate change are driven by social characteristics. For example, take two groups’ responses to the question of what the main driver of climate change is—climate scientists and overburdened communities. A group of climate scientists might overwhelmingly respond with something like, “greenhouse gas emissions.” From this perspective, reducing greenhouse gas emissions is the most effective measure to mitigate climate change. However, according to the report, individuals from overburdened communities that have not benefited as much from industrialization might alternatively say that the fundamental cause of climate change is the prevailing socioeconomic and ethical arrangement of society that allows for the exploitation of the environment and people. According to this perspective, re-envisioning social systems in a more just way is essential to mitigating climate change.

Robust climate mitigation and adaptation, the NCA5 chapter continues, requires multiple perspectives, including those of climate scientists, traditional Indigenous knowledge holders, and multi-generational farmers, among other climate-affected groups. Taking all of these perspectives into consideration allows for the coproduction of knowledge, which is our best shot at informing climate governance that works for all people, places, and the planet.

As regular readers of ELI materials know, climate change is already driving large shifts throughout global society. In the NCA5 chapter, special attention is paid to two of these shifts: human migration and the energy transition. The chapter notes that climate justice should inform these two massive transformations to society are carried out in an equitable way.

The relocation of individuals or communities in the face of climate hazards—such as extreme heat, sea-level rise, and hurricanes—ought to be governed within the framework of climate justice. As the chapter indicates, just climate migration should include community-based decision-making and a redress of historical wrongs to foster an equitable distribution of risk and resilience. The Quinault Indian Nation provides an example of what this looks like in practice, according to the report. To mitigate flood risks posed to its village, the Quinault Indian Reservation co-developed a strategy with the community and outside planners to relocate in 2014. This kind of participatory decision-making is an essential piece of equitable migration under climate change.

The chapter also indicates that it is imperative that justice be built into the framework of changes to our country’s energy sector, as it shifts away from fossil fuels. Without training and access to opportunities in the new green economy, workers from the coal, oil, and gas industries will lose employment. These issues must be addressed in equitable transition policies, like Colorado’s Just Transition Action Plan, according to the report.

Equally important, the chapter continues, is that overburdened individuals, such as those from low-income and BIPOC communities, benefit from the transition and do not continue to bear a disproportionate share of the harms from environmental degradation. When developing and deploying green infrastructure, decision-makers should give explicit consideration to the impacts on and benefits to these communities. The chapter identifies the Biden Administration’s Justice40 Initiative, which aims to deliver 40% of the benefits of climate investments to disadvantaged groups, as an example of how climate justice can be incorporated into federal decision-making.

As climate change inevitably continues to reshape social systems throughout the United States, it will be up to our nation’s decision-makers—including judges—to determine if those changes are made in an equitable manner.